Tuesday, July 18, 2006

A Portrait of the Zambian People

The kindness and generosity of the Zambian people are even more remarkable considering how poor they truly are. There are few jobs and ''sponsors" for higher education are equally scarce. The government is useless to solve these problems, dependent on foreign donors and grappling with corruption. Everything is a process and the people must work earnestly to overcome the constant breaks and delays. That is, the Zambian women do. Far too many of the men spend their days in the bar, no doubt depressed by their dreary future. In contrast though, the women are always busy cooking, cleaning, shopping, raising the children, even farming their small, arid plots and selling the harvest. For their effort they must watch their children go hungry and run about in tatters. If they are lucky. In Zambia the Infant Mortality Rate is a whopping 200 per 1,000 children and another 1.2 million people are infected by HIV/AIDS. No wonder life expectancy has been recorded as low as 33 years old.

The kindness and generosity of the Zambian people are even more remarkable considering how poor they truly are. There are few jobs and ''sponsors" for higher education are equally scarce. The government is useless to solve these problems, dependent on foreign donors and grappling with corruption. Everything is a process and the people must work earnestly to overcome the constant breaks and delays. That is, the Zambian women do. Far too many of the men spend their days in the bar, no doubt depressed by their dreary future. In contrast though, the women are always busy cooking, cleaning, shopping, raising the children, even farming their small, arid plots and selling the harvest. For their effort they must watch their children go hungry and run about in tatters. If they are lucky. In Zambia the Infant Mortality Rate is a whopping 200 per 1,000 children and another 1.2 million people are infected by HIV/AIDS. No wonder life expectancy has been recorded as low as 33 years old.33. How did we get here? Surprise, surprise it started with the English colonizers who exploited the country's natural resources, sending the wealth south to develop their other more desirable colonies. Independence changed the cast of criminals with a new local elite, the IMF and World Bank, and even aid donors taking the Brits place. There was always something: droughts, a plunge in copper prices (Zambia's main export), a rigged international agricultural market, the devestating HIV/AIDS pandemic. Truly, Zambia has never gotten a fair chance. Still, with 70 some ethnic groups the country has remained a much needed oasis of peace in a troubled region, living up to its proud self-designation as a "Christian nation."

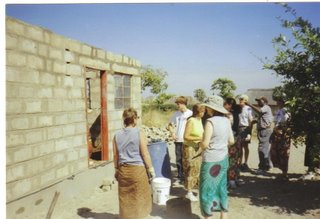

There are bright spots then, some of which I was blessed to take a part in in aformentioned Kaoma. I first arrived in town with a Habitat for Humanity trip of 20 Americans, helping to build a house from foundation to finish in less than a week. Habitat makes it possible for people to upgrade from the traditional (and rapidly deteriorating) huts to the small but sturdy western structures. In most cases these houses would be prohibitively expensive but Habitat essentially grants no-interest loans, allowing homeowners to pay back the cost in the form of a bag of cement every month (for about ten years). Another impressive organization was the Women's Empowerment Center, training and selling women's crafts among other community projects. Or Sister Mary from Ireland who had built a virtual empire of orphanages, a community school, affordable housing, and projects like a farm and guesthouse to provide some attempt at sustainability. An easy life by no means, these orphans did seem happy and were in fact better off than most local children thanks to Sister Mary, Rita, and the selfless efforts of many others.

Several times I was asked how we can reconcile these two pictures: are Zambian s happy or not? My friend Lynn who knows Zambia well suggested that many of the people we saw were happy because they were able to see us, a theory I agree with. But I also think that it goes further than this and the Zambian people have their moments of happiness even when we aren't there. Despite their poverty, Zambians have managed to find richness in their interactions with others, in community. Indeed, here they are rich where we in the USA are poor.

s happy or not? My friend Lynn who knows Zambia well suggested that many of the people we saw were happy because they were able to see us, a theory I agree with. But I also think that it goes further than this and the Zambian people have their moments of happiness even when we aren't there. Despite their poverty, Zambians have managed to find richness in their interactions with others, in community. Indeed, here they are rich where we in the USA are poor.

So where does this leave us? Does it all balance out so that we don't have to worry about the poor Zambians? You probably can tell that my answer is no. Their sense of community doesn not make their suffering any less. I wouldn't wish the struggle of their daily lives on anyone, especially not such a beautiful people as these. Let me close with this. Although English is the national language, for some in Kaoma their conversation is limited to "How are you?" always followed by "I'm fine." For the first several weeks I tried unsuccessfully to teach them to progress from the state of "fine" to "good." That is until I realized they were speaking the truth; they are merely fine. My wish then is still for them to be "good," for their lives to be less of a struggle, and for the moments of happiness to come just a little easier.