Tuesday, January 16, 2007

East Africa And Back

Well, I am home! Looking back on this blog I wish that I had been able to post a little more frequently, but figured that I can at least make some amends by adding a few of my pictures and wrapping up on the last few months. Here is the fruit of my efforts.

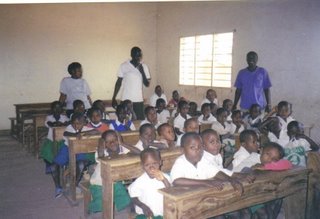

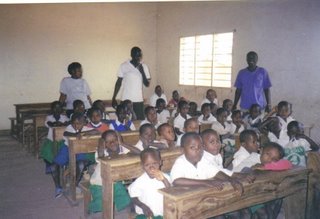

After our visit with Watema Emmanuel we had a couple of two-week service projects. The first of these was right outside of Lugufu Refugee Camp in Kigoma, Tanzania. We were working with a local organization called KIVIDEA that worked with youth to help alleviate poverty. Schools, farms, youth groups -- they were really tackling the problem from every angle. Our other project was in Kiganda, Uganda (a couple of long hard travel days north..) Father Achilles Kiwanuka, an acquaintance from the University of Portland was our host, putting us up with his parents (and

After our visit with Watema Emmanuel we had a couple of two-week service projects. The first of these was right outside of Lugufu Refugee Camp in Kigoma, Tanzania. We were working with a local organization called KIVIDEA that worked with youth to help alleviate poverty. Schools, farms, youth groups -- they were really tackling the problem from every angle. Our other project was in Kiganda, Uganda (a couple of long hard travel days north..) Father Achilles Kiwanuka, an acquaintance from the University of Portland was our host, putting us up with his parents (and  quite comfortably too!) Kelly worked at the primary school around the corner, I at the local clinic. The small staff here did great work attempting to deal with the volume of malaria and AIDS cases considering their limited resources. Most amusingly, word got out that the clinic now had a white doctor and patients started coming in from hours away to see me!

quite comfortably too!) Kelly worked at the primary school around the corner, I at the local clinic. The small staff here did great work attempting to deal with the volume of malaria and AIDS cases considering their limited resources. Most amusingly, word got out that the clinic now had a white doctor and patients started coming in from hours away to see me!

The 10th and final country on my itinerary was tiny Rwanda, landlocked outside of its own Lake Kivu. As covered in a previous post, in 1994 the fastest, and arguably most brutal, genocide in the history of the world saw one million Tutsi's die at the hands of the extremist Hutu government. Much of our ten day tour around the country centered around this event, including a beautiful Memorial Center in Kigali and a haunting church where one of the slaughters took place. However, as horrible as their history has been, Rwandans were proving a hardy lot. Amazingly, thanks to a competent government, Rwanda truly seemed on the right path to peace and prosperity. (My trip here did indeed confirm my first impression from visiting the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda that the UN trial was for the world, and the gacaca trials were for the Rwandans... a disconnect that needs to be better bridged by the ICT.)

Our last days of traveling were as enjoyable as ever, and we especially enjoyed the people and green landscapes of Uganda. Lake Bunyoni, the Rwenzori Mountains, Bujugali Falls on the Nile River, and Sipi Falls were among the most beautiful sites I had visited. Back in Kenya, trips to Lake Naivasha, the nearby Hell's Gate National Park, and of course, safari at Masai Mara Game Reserve were pleasant if slightly too touristy for my taste. And successful navigation of Nairobi meant that I made it through the whole trip and only been robbed once (by street kids in Cape Town...) Our flight home was a long one (after a detour to Sudan separated us from our bags) but also a comfortable one compared to the 10,000 miles spent on some less than stellar roads in Africa!

Reserve were pleasant if slightly too touristy for my taste. And successful navigation of Nairobi meant that I made it through the whole trip and only been robbed once (by street kids in Cape Town...) Our flight home was a long one (after a detour to Sudan separated us from our bags) but also a comfortable one compared to the 10,000 miles spent on some less than stellar roads in Africa!

I don't think I have to tell you that I had an incredible time. I was able to see some really spectacular places over these eight months, from Victoria Falls to Mount Kilimanjaro, but more importantly, meet some really spectacular people. All five of my longer service projects taught me a lot about the depth of the problems people are facing and, when I was really lucky, the corresponding solutions. This couldn't have happened without a whole lot of hospitality on the part of the people I met (and quite a few of you as well since I was often contacting a friend of a friend...) It goes without saying that I hope to return in the future to repay some of this debt.

I want to thank all of you that followed my trip as well as those who have just stumbled upon my blog. Please feel free to contact me if you want to talk more about any of these issues or especially if you are thinking of traveling and are wondering how you could arrange some independent volunteer projects as well. I would be happy to help and wish that everyone could have to opportunity to learn about the world by traveling as I have.

After our visit with Watema Emmanuel we had a couple of two-week service projects. The first of these was right outside of Lugufu Refugee Camp in Kigoma, Tanzania. We were working with a local organization called KIVIDEA that worked with youth to help alleviate poverty. Schools, farms, youth groups -- they were really tackling the problem from every angle. Our other project was in Kiganda, Uganda (a couple of long hard travel days north..) Father Achilles Kiwanuka, an acquaintance from the University of Portland was our host, putting us up with his parents (and

After our visit with Watema Emmanuel we had a couple of two-week service projects. The first of these was right outside of Lugufu Refugee Camp in Kigoma, Tanzania. We were working with a local organization called KIVIDEA that worked with youth to help alleviate poverty. Schools, farms, youth groups -- they were really tackling the problem from every angle. Our other project was in Kiganda, Uganda (a couple of long hard travel days north..) Father Achilles Kiwanuka, an acquaintance from the University of Portland was our host, putting us up with his parents (and  quite comfortably too!) Kelly worked at the primary school around the corner, I at the local clinic. The small staff here did great work attempting to deal with the volume of malaria and AIDS cases considering their limited resources. Most amusingly, word got out that the clinic now had a white doctor and patients started coming in from hours away to see me!

quite comfortably too!) Kelly worked at the primary school around the corner, I at the local clinic. The small staff here did great work attempting to deal with the volume of malaria and AIDS cases considering their limited resources. Most amusingly, word got out that the clinic now had a white doctor and patients started coming in from hours away to see me!The 10th and final country on my itinerary was tiny Rwanda, landlocked outside of its own Lake Kivu. As covered in a previous post, in 1994 the fastest, and arguably most brutal, genocide in the history of the world saw one million Tutsi's die at the hands of the extremist Hutu government. Much of our ten day tour around the country centered around this event, including a beautiful Memorial Center in Kigali and a haunting church where one of the slaughters took place. However, as horrible as their history has been, Rwandans were proving a hardy lot. Amazingly, thanks to a competent government, Rwanda truly seemed on the right path to peace and prosperity. (My trip here did indeed confirm my first impression from visiting the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda that the UN trial was for the world, and the gacaca trials were for the Rwandans... a disconnect that needs to be better bridged by the ICT.)

Our last days of traveling were as enjoyable as ever, and we especially enjoyed the people and green landscapes of Uganda. Lake Bunyoni, the Rwenzori Mountains, Bujugali Falls on the Nile River, and Sipi Falls were among the most beautiful sites I had visited. Back in Kenya, trips to Lake Naivasha, the nearby Hell's Gate National Park, and of course, safari at Masai Mara Game

Reserve were pleasant if slightly too touristy for my taste. And successful navigation of Nairobi meant that I made it through the whole trip and only been robbed once (by street kids in Cape Town...) Our flight home was a long one (after a detour to Sudan separated us from our bags) but also a comfortable one compared to the 10,000 miles spent on some less than stellar roads in Africa!

Reserve were pleasant if slightly too touristy for my taste. And successful navigation of Nairobi meant that I made it through the whole trip and only been robbed once (by street kids in Cape Town...) Our flight home was a long one (after a detour to Sudan separated us from our bags) but also a comfortable one compared to the 10,000 miles spent on some less than stellar roads in Africa!I don't think I have to tell you that I had an incredible time. I was able to see some really spectacular places over these eight months, from Victoria Falls to Mount Kilimanjaro, but more importantly, meet some really spectacular people. All five of my longer service projects taught me a lot about the depth of the problems people are facing and, when I was really lucky, the corresponding solutions. This couldn't have happened without a whole lot of hospitality on the part of the people I met (and quite a few of you as well since I was often contacting a friend of a friend...) It goes without saying that I hope to return in the future to repay some of this debt.

I want to thank all of you that followed my trip as well as those who have just stumbled upon my blog. Please feel free to contact me if you want to talk more about any of these issues or especially if you are thinking of traveling and are wondering how you could arrange some independent volunteer projects as well. I would be happy to help and wish that everyone could have to opportunity to learn about the world by traveling as I have.

Monday, November 20, 2006

Watema Emmanuel

It took a day of negotiating some tedious government beauracracy, two on a train across Tanzania, and a lift from the UN, but we succeeded in one of my goals for the trip: visit my Congolese friends in Lugufu Refugee Camp. It was back in 2003 that a group of 18 students from Semester at Sea and I were able to meet and hear the stories of these six young men. My friend Watema Emmanuel's story was fairly typical: in 1998 his village in Eastern Congo came under attack by one of the militias in Africa's first World War. Only 12 at the time, he witnessed the murder of both of his parents and lost contact with his other relatives in the following escape to Tanzania. It is here that he has lived alone for the past eight years, managing to continue his education even through a serious bout with malaria last year.

It took a day of negotiating some tedious government beauracracy, two on a train across Tanzania, and a lift from the UN, but we succeeded in one of my goals for the trip: visit my Congolese friends in Lugufu Refugee Camp. It was back in 2003 that a group of 18 students from Semester at Sea and I were able to meet and hear the stories of these six young men. My friend Watema Emmanuel's story was fairly typical: in 1998 his village in Eastern Congo came under attack by one of the militias in Africa's first World War. Only 12 at the time, he witnessed the murder of both of his parents and lost contact with his other relatives in the following escape to Tanzania. It is here that he has lived alone for the past eight years, managing to continue his education even through a serious bout with malaria last year.We had kept in touch since but he was not expecting me since my last letter predicted I wouldn't arrive at the camp for another month. It was a joyful reunion, especially when we were also able to visit with the other friends I had made on my first trip to Tanzania. Even without any notice my friends were able to rassle up a vehicle from one of the Non-Gove

rnmental Organizations (NGO's) in order to give us the grand tour of the camp... no small favor since with two camps of 32 villages and tens of thousands of refugees this was a pretty big place. Indeed, these dusty mud huts spread out in a neat grid for as far as you could see, only occassionally broken up by a water station or school or some such thing. Without any jobs, the camp was pervaded by a sense of waiting for something. Needless to say it was a very impoverished, depressing place on the whole.

rnmental Organizations (NGO's) in order to give us the grand tour of the camp... no small favor since with two camps of 32 villages and tens of thousands of refugees this was a pretty big place. Indeed, these dusty mud huts spread out in a neat grid for as far as you could see, only occassionally broken up by a water station or school or some such thing. Without any jobs, the camp was pervaded by a sense of waiting for something. Needless to say it was a very impoverished, depressing place on the whole.Being a refugee is about the worst position in the world to find yourself. You can't leave the camp to enter the country, you can't go back home to the war-zone. You have no country. You have no freedom. You are a prisoner. Confronted by this start reality, the group of students and

I couln't help but try to draw some lessons of how to help with this situation. I was surprised to realize that however simple they may be, our answer is as true today as ever. First, we must support the efforts of the international community to care for the refugees. The UN High Commision for Refugees, Red Cross, World Vision... without these NGO's the refugees would quite simply die; not an exageration since these refugees found themselves forced into a barren wasteland.

I couln't help but try to draw some lessons of how to help with this situation. I was surprised to realize that however simple they may be, our answer is as true today as ever. First, we must support the efforts of the international community to care for the refugees. The UN High Commision for Refugees, Red Cross, World Vision... without these NGO's the refugees would quite simply die; not an exageration since these refugees found themselves forced into a barren wasteland.Secondly, and more dauntingly, we must do our part to prevent war. That is how refugee crises start. War becomes even less of an acceptable option when we realize how totally it ruins the lives of those it touches. Fortunately, the Democratic Republic of Congo appears to finally be emerging from its five year conflict that claimed a staggering four million lives. The first elections in over forty years were completed last week with Joseph Kabila winning the presidency in relatively peaceful elections (but hold your breath...) If the peace holds, and if we can further strengthen the international community, perhaps Watema and the fifteen million refugees like him will live to see better days.

Friday, October 13, 2006

Quote

"We spend a lot of time talking about Africa, as we should. Africa is a nation that suffers from incredible disease." -- President George W. Bush

Our President is correct that disease is a very real problem in Africa. However, while we should spend a lot of time talking about Africa, we do not. But most importantly, AFRICA IS NOT A NATION! AFRICA IS A CONTINENT MADE UP OF 53 DIVERSE, DISTINCTIVE NATIONS! AFRICA... IS NOT... A COUNTRY!!!

Our President is correct that disease is a very real problem in Africa. However, while we should spend a lot of time talking about Africa, we do not. But most importantly, AFRICA IS NOT A NATION! AFRICA IS A CONTINENT MADE UP OF 53 DIVERSE, DISTINCTIVE NATIONS! AFRICA... IS NOT... A COUNTRY!!!

Friday, September 29, 2006

Traveling in the Islamic World

Over the last two weeks I have been traveling along the Kenyan and Tanzanian coast with my recently arrived girlfriend, Kelly. This has been especially interesting with its fascinating Swahili culture and overwhelmingly Muslim population. Given the state of affairs in the world, I feel as though at least a few words should be said on this.

Over the last two weeks I have been traveling along the Kenyan and Tanzanian coast with my recently arrived girlfriend, Kelly. This has been especially interesting with its fascinating Swahili culture and overwhelmingly Muslim population. Given the state of affairs in the world, I feel as though at least a few words should be said on this.Until I caught a snippet of CNN the other night I had missed the story of Pope Benedict's inflammatory comments on Islam and almost forgotten about the quagmire of Iraq. All this despite the fact that I was traveling in the Islamic world for the first time. The reason for this is simple: it is totally and completely peaceful here.

When I arrived on the island of Lamu I was told that there was no crime here since everyone was Muslim. The same proved true for the much larger and more chaotic Zanzibar. Yes, it was nice that it was safe enough to walk at night, but more than that, it was actually peaceful. Things move nice and slowly here -- even the touts pushing curios to the tourists seemed a little more relaxed. Indeed, people seemed even more friendly than normal, with calls of "Karibu," or you are welcome, following us everywhere.

And this in a very conservative society. Most women wear ninja's, a garment that covers all but their eyes. The men for their part don't drink or smoke, dutifully reporting to

the nearest mosque for each of the five daily prayers. Residents dedication to Islam became even more pronounced with the start of the daily fasts of Ramadan. In an effort at solidarity we tried it ourselves one day, and let me tell you it is no easy task in this heat!

the nearest mosque for each of the five daily prayers. Residents dedication to Islam became even more pronounced with the start of the daily fasts of Ramadan. In an effort at solidarity we tried it ourselves one day, and let me tell you it is no easy task in this heat!So when I see clips of protesters in the streets over the Pope's remarks, I can't help but wonder why things don't look like that here. Why don't I see T-shirts of Osama bin Laden or graffiti protesting Iraq (almost everyone here belongs to Sadaam's Sunni sect)? Yes, Africans tend to be more pro-US than most, but this is more than politics: I am living in a seemingly entirely different picture than the one I see on CNN.

Here is my point: the pictures we see coming out of the Middle East are not telling the whole picture. Muslims are very upset by what they see (quite fairly) as persecution by the US. However, few make their politics personal and seem to inately recognize the difference between disliking the US government and disliking Americans. More importantly, Islam is not the violent religion that our media, government, and terrorists would like to think it is. It is an easy lesson to forget, and one I hope I won't when I return home to the states and those CNN clips.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

I love Tanzania and am happy to be back, especially given that I now know a little more Swahili than I did when I came three years ago. So I hate to skip over talking about the country in favor of another but that is exactly what I am going to have to do. For when I was in Arusha in northern Tanzania I sat in on the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR.)

The ICTR was mandated by the United Nations to prosecute those who mastermided the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in which over 800,000 people were killed. The crime of genocide is any action that has the intent of destroying a particular group of people (in this case it was Tutsi's and moderate Hutu's, the two main tribes in Rwanda.) Some time has passed since the first trial started in 1997, so it is not surprising that individual don or nations (the US in particular) have grown tired of pumping millions into this never-ending process and have insisted that the entire process be completed within the next two years. However, on my arrival they were exactly half-way done: 28 trials down (25 convictions and 3 acquitals), 28 to go. The guilty plea and conviction of former Prime Minister Kambanda were both firsts; quite literally this court was history in the making.

or nations (the US in particular) have grown tired of pumping millions into this never-ending process and have insisted that the entire process be completed within the next two years. However, on my arrival they were exactly half-way done: 28 trials down (25 convictions and 3 acquitals), 28 to go. The guilty plea and conviction of former Prime Minister Kambanda were both firsts; quite literally this court was history in the making.

It was quite a process getting through security and all, especially given my unintended but interesting detour into a locked down wing of the building. After escaping I was given a headset that translated the proceedings into three languages (English, French, and Kinyarwanda) and shown into the glassed-in viewing room. The courtrooms were very nice, and crowded with a wide array of technology and lawyers. Obviously attire was formal with lots of black robes, red vestments, white scarves, and even a few old fashioned whigs. Even the supposedly "indigent" accused sported fancy suits and nice watches; indeed, this trial in Tanzania would be the best they could hope for for the rest of their lives...

The first case I observed was wrought with theatrical legal wrangling and discrepencies over page numbers, but was quite fascinating when they got down to the business at hand. The witness had written a book about his experience during the genocide, and interestingly, he was there as a defense witness for one of the accused despite losing several of his own family members in the killing. The other trial that I followed was hearing its 67th witness, a woman who's husband had been a prominent politican and was killed immediately after the fighting began. She spoke poignantly about the events of that day, from the UN's abandonment of 2,000 refugees to his soon-after abduction by members of the Presidential Guard. The woman clearly placed blame both at the feet of the accused and the very institution that was trying them (more on this in a minute.) On the cross-examination the defence desperately threw up several alternative theory's to her story, none of them convincing anyone.

When one of my fellow observers asked for my thoughts on the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda over lunch, she got an earful. Namely the troubling starting point of the same international body that failed to stop the genocide being placed in the position of determining who was responsible for the murder of the 800,000 Rwandans. This fact created a dangerous dynamic in which the court had an inherent motive of wanting to convict and blame the accused. And this in a conflict that I believed was more a chaotic orgy of killing than a well-ordered master plot for genocide; one of the witnesses insisted on using the term "hoodlum" rather than genocidaire for this very reason. That said, there is a need to hold the bosses accountable and strike a blow to the "culture of impunity" and blind obediance to authority that the court said allowed the genocide to occur. In many ways this would be the biggest impact that the court could hope to have, seeking to deter future human rights abuses with the message that leaders would be brought to (western) justice. Or as my lunch-date and I concluded, the world needed the ICTR, Rwandan's needed the gacacas, or the traditional courts operating back home. But I will be a little more confident in this opinion once I visit the country for myself next month...

The ICTR was mandated by the United Nations to prosecute those who mastermided the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in which over 800,000 people were killed. The crime of genocide is any action that has the intent of destroying a particular group of people (in this case it was Tutsi's and moderate Hutu's, the two main tribes in Rwanda.) Some time has passed since the first trial started in 1997, so it is not surprising that individual don

or nations (the US in particular) have grown tired of pumping millions into this never-ending process and have insisted that the entire process be completed within the next two years. However, on my arrival they were exactly half-way done: 28 trials down (25 convictions and 3 acquitals), 28 to go. The guilty plea and conviction of former Prime Minister Kambanda were both firsts; quite literally this court was history in the making.

or nations (the US in particular) have grown tired of pumping millions into this never-ending process and have insisted that the entire process be completed within the next two years. However, on my arrival they were exactly half-way done: 28 trials down (25 convictions and 3 acquitals), 28 to go. The guilty plea and conviction of former Prime Minister Kambanda were both firsts; quite literally this court was history in the making.It was quite a process getting through security and all, especially given my unintended but interesting detour into a locked down wing of the building. After escaping I was given a headset that translated the proceedings into three languages (English, French, and Kinyarwanda) and shown into the glassed-in viewing room. The courtrooms were very nice, and crowded with a wide array of technology and lawyers. Obviously attire was formal with lots of black robes, red vestments, white scarves, and even a few old fashioned whigs. Even the supposedly "indigent" accused sported fancy suits and nice watches; indeed, this trial in Tanzania would be the best they could hope for for the rest of their lives...

The first case I observed was wrought with theatrical legal wrangling and discrepencies over page numbers, but was quite fascinating when they got down to the business at hand. The witness had written a book about his experience during the genocide, and interestingly, he was there as a defense witness for one of the accused despite losing several of his own family members in the killing. The other trial that I followed was hearing its 67th witness, a woman who's husband had been a prominent politican and was killed immediately after the fighting began. She spoke poignantly about the events of that day, from the UN's abandonment of 2,000 refugees to his soon-after abduction by members of the Presidential Guard. The woman clearly placed blame both at the feet of the accused and the very institution that was trying them (more on this in a minute.) On the cross-examination the defence desperately threw up several alternative theory's to her story, none of them convincing anyone.

When one of my fellow observers asked for my thoughts on the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda over lunch, she got an earful. Namely the troubling starting point of the same international body that failed to stop the genocide being placed in the position of determining who was responsible for the murder of the 800,000 Rwandans. This fact created a dangerous dynamic in which the court had an inherent motive of wanting to convict and blame the accused. And this in a conflict that I believed was more a chaotic orgy of killing than a well-ordered master plot for genocide; one of the witnesses insisted on using the term "hoodlum" rather than genocidaire for this very reason. That said, there is a need to hold the bosses accountable and strike a blow to the "culture of impunity" and blind obediance to authority that the court said allowed the genocide to occur. In many ways this would be the biggest impact that the court could hope to have, seeking to deter future human rights abuses with the message that leaders would be brought to (western) justice. Or as my lunch-date and I concluded, the world needed the ICTR, Rwandan's needed the gacacas, or the traditional courts operating back home. But I will be a little more confident in this opinion once I visit the country for myself next month...

Monday, September 04, 2006

Malawi

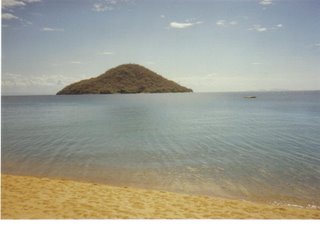

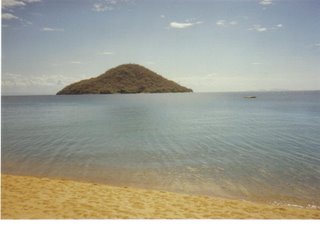

"Give me money!" "Give me sweet!" "Give me pen!" "Where is my pension?" These were the calls that followed me throughout Malawi. Not only from children either, with adults getting into the act, asking me to buy them new shoes, put them through school, or even build them a church or a school! This is not to imply that they weren't present in other countries, but they seemed especially constant in this small southern African country, self-dubbed "the warm heart of Africa" (which, I should note, in many ways it is with friendly, outgoing, hospitable people...) These pleas shouldn't be surprising given that most Malawians live on a dollar a day and that mzungus (whites) have deep (or at least relatively deep) pockets. What concerns me though is how these fairly innocent statements point to a sense of dependency on, entitlement to, and helplessness without handouts from others. That can have a very real and debilitating effect on a culture. So where does this come from? Was it from the tourists? The aid workers? To me each group seemed to be equal contributors to this problem (not an exciting prospect as I managed to qualify as both of these culprits...)

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

The mixed results of foreign aid goes back even further. For three decades western donors purposely propped up repressive dictator Dr. Hastings Banda (a product of the US education system) as a bulkhead against the otherwise socialist tendencies of the region. This is an extreme case but studies show little immediate growth and most damningly, negative results in the long term. The problem with development is that it is ultimately self-interested, coming with many strings attached. Development groups hire their own compatriots so few of their dollars or know-how trickle down to the locals in need. They focus on the sexy projects -- bridges, power-plants, etc. -- failing to provide for the equally pressing needs maintainance and renovation. So things fall apart. And all of this is approached in a top-down manner; locals are not asked what they need, but rather told what they much do. This assumes that western culture has a monopoly on the knowledge of how a society should develop (because we haven't made any mistakes...) So foreign labor, surpluses, and dollars are sunk into various holes in the country with pitiful results, which are blamed on poor execution and even a bad work-ethic on the part of the local recipients. In truth most of the blame lies with this backwards approach to giving aid, encouraging these values of dependency, entitlement, and helplessness.

As I said these are not easy revelations for me. I firmly believe in the importance of experiencing and learning about other cultures as well as the need for rich countries to commit their resources to assisting the poorer nations of the world. And I still do. Once again we must beware the false morals of cynics who would tell us to disengage entirely and instead search for a better solution. There are both good and bad ways of doing most anything; tourism and foreign aid are no exception. What we really need is to reevaluate our current approach. Tourists must be more mindful of the impact of their actions and how they spend their dollars. Aid organizations must seek solutions from the people, empowering them to help themselves. And most importantly, both must put the interest of the Malawian people first in their minds and actions that follow. At that point we foreigners may actually be able to contribute favorably, finally allowing Malawi to become independent, self-sufficient, and prosperous. In the eyes of this traveler-volunteer that would be a much nicer legacy.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.The mixed results of foreign aid goes back even further. For three decades western donors purposely propped up repressive dictator Dr. Hastings Banda (a product of the US education system) as a bulkhead against the otherwise socialist tendencies of the region. This is an extreme case but studies show little immediate growth and most damningly, negative results in the long term. The problem with development is that it is ultimately self-interested, coming with many strings attached. Development groups hire their own compatriots so few of their dollars or know-how trickle down to the locals in need. They focus on the sexy projects -- bridges, power-plants, etc. -- failing to provide for the equally pressing needs maintainance and renovation. So things fall apart. And all of this is approached in a top-down manner; locals are not asked what they need, but rather told what they much do. This assumes that western culture has a monopoly on the knowledge of how a society should develop (because we haven't made any mistakes...) So foreign labor, surpluses, and dollars are sunk into various holes in the country with pitiful results, which are blamed on poor execution and even a bad work-ethic on the part of the local recipients. In truth most of the blame lies with this backwards approach to giving aid, encouraging these values of dependency, entitlement, and helplessness.

As I said these are not easy revelations for me. I firmly believe in the importance of experiencing and learning about other cultures as well as the need for rich countries to commit their resources to assisting the poorer nations of the world. And I still do. Once again we must beware the false morals of cynics who would tell us to disengage entirely and instead search for a better solution. There are both good and bad ways of doing most anything; tourism and foreign aid are no exception. What we really need is to reevaluate our current approach. Tourists must be more mindful of the impact of their actions and how they spend their dollars. Aid organizations must seek solutions from the people, empowering them to help themselves. And most importantly, both must put the interest of the Malawian people first in their minds and actions that follow. At that point we foreigners may actually be able to contribute favorably, finally allowing Malawi to become independent, self-sufficient, and prosperous. In the eyes of this traveler-volunteer that would be a much nicer legacy.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Anecdotes

I am aware that my rambling, bookish posts can be tedious in the best of times and mind-numbingly boring in the worst... so here are arguably the three most interesting stories that I have for the past month of travels.

#3: Visiting the Cheif

A month and a half into working in the town of Kaoma in western Zambia, I figured it was time to pay a visit to the cheif. After booking an appointment and slogging for a couple of hours along a sandy road leading out of town, my contingent of three friends and I arrived at the palace of the districts senior cheif and member of the Lozi royal family, Cheif Isititeketo. While waiting for the okay to enter from one of the court's pages I met with the Prime Minister, who needled my about being related to Ian Smith (the racist ex-dictator of neighboring Zimbabwe.) Eventually we entered the walled palace (my friend Margaret went through a seperate door since "she has periods") to the cheif's home. But first we had to kneel and clap half-a-dozen times on the way to his throne, where we dropped to a crawl up to his feet. The cheif, a stout grandfatherfly looking man shook my hand and gestured for me to sit, while the others were left to grovel for a little while longer. I talked briefly about my volunteer projects in Kaoma, but this was his show and he quickly steered the conversation to his favorite topic: the United States. He had gone to school in California and was eager to reminisce and even talk a little politics (I got in a couple of good digs at Bush.) Some 45 minutes later it was time for me to present our gift, a woven basket and tie-dyed material from the local Women's Center. He liked it. Exchanging pleasantries, we crawled backwards (harder than it sounds), periodically clapping our way out of the palace. This was my brush with royalty.

#2: The Tobacco Floors

In Malawi tobacco accounts for two-thirds of their foreign currency earnings; a critical chunk of the economy, and one which I wanted a closer look at. Boarding a mini-bus I weaved my way north through the streets of the capital Lilongwe to my destination: the Kenango Industrial Compound. Luckily, it was a windy day and I was able to follow my nose (and the sweet smell of tobacco) to the auction floors. Here a smartly-dressed worker named Maxwell whisked me past security to his post in the loading docks. Trucks, trains, and conveyer belts waited here to rush the recently purchased bags to nearby processing factories. We were refused a tour on such short notice so I stealthily snuck past the lines of growers waiting for their pay into the massive, airplane hangar sized auction floor. On a walkway suspended above the floor I watched bare-chested men racing to and fro with the bursting burlap bags of tobacco on dolleys. It didn't take much coaxing for me to jump down to help out and the hall lit up with hoots as I charged with my load the length of a football field, twenty men in V-formation behind me! Really fun. The stern looking boss told me I had read my UPC code wrong and this bag was in the wrong spot. After righting this wrong he broke into a smile and told me to be in the next morning at 5 am for work. So, hey, if things don't work out when I get back to the States I always have a job waiting for me with big tobacco, at a cool $2 per day!

#1: Mother Tiger

It started as an innocent trip to go see Kazanga, a traditional ceremony of the Nkoya tribe of northwestern Zambia. Brother Rogers, Brother Peter, (former) Father Ronald and I walked a good distance out of town to the field where the festivities were being held. We didn't stay more than an hour (the crowds of drunken young men were a bit too much for my holy companions) but I did get a chance to cause a scene by joining one of the performance groups dancing in the main arena. On the way out we helped push a little pickup truck named Mother Tiger that had stalled outside the main gate. Next thing we knew we were speeding downhill back towards town. It was then that Br. Peter said he didn't think that the truck had any breaks. Fr. Ronald added that he knew the man driving as a drunk. I immediately dismissed these comments: how could this man be taxying people to and from Kazanga all day if he had no breaks? I mean, what would he do when he met someone on the one-lane bridge at the bottom of the hill?! Of course, we barreled onto the bridge with a shiny SUV already half-way across. The other driver flashed his lights and beeped the horn; since we had neither of these our driver simply started yelling out his window. As I braced myself for the impact Br. Rogers jumped overboard at a run, managing to stay both on his feet and out of the river some twenty feet below. Fortunately the other driver started to reverse so the crash wasn't too violent, with the guardrails easing us back off the bridge. Nevertheless, the grill of the new SUV was badly damaged and as the men began to push my driver for his stupidity I feared they would beat him bloody. Since everyone was unharmed they contented themselves to haul Mother Tiger and its owner into the police station. My friends and I had a good laugh after fleeing the scene of the crime. But when they began to blame the fact that the bridge only had one-lane, I had to interject. Mother Tiger had to accept at least partial responsibility. They shrugged their shoulders, afterall, this was transportation in Zambia.

#3: Visiting the Cheif

A month and a half into working in the town of Kaoma in western Zambia, I figured it was time to pay a visit to the cheif. After booking an appointment and slogging for a couple of hours along a sandy road leading out of town, my contingent of three friends and I arrived at the palace of the districts senior cheif and member of the Lozi royal family, Cheif Isititeketo. While waiting for the okay to enter from one of the court's pages I met with the Prime Minister, who needled my about being related to Ian Smith (the racist ex-dictator of neighboring Zimbabwe.) Eventually we entered the walled palace (my friend Margaret went through a seperate door since "she has periods") to the cheif's home. But first we had to kneel and clap half-a-dozen times on the way to his throne, where we dropped to a crawl up to his feet. The cheif, a stout grandfatherfly looking man shook my hand and gestured for me to sit, while the others were left to grovel for a little while longer. I talked briefly about my volunteer projects in Kaoma, but this was his show and he quickly steered the conversation to his favorite topic: the United States. He had gone to school in California and was eager to reminisce and even talk a little politics (I got in a couple of good digs at Bush.) Some 45 minutes later it was time for me to present our gift, a woven basket and tie-dyed material from the local Women's Center. He liked it. Exchanging pleasantries, we crawled backwards (harder than it sounds), periodically clapping our way out of the palace. This was my brush with royalty.

#2: The Tobacco Floors

In Malawi tobacco accounts for two-thirds of their foreign currency earnings; a critical chunk of the economy, and one which I wanted a closer look at. Boarding a mini-bus I weaved my way north through the streets of the capital Lilongwe to my destination: the Kenango Industrial Compound. Luckily, it was a windy day and I was able to follow my nose (and the sweet smell of tobacco) to the auction floors. Here a smartly-dressed worker named Maxwell whisked me past security to his post in the loading docks. Trucks, trains, and conveyer belts waited here to rush the recently purchased bags to nearby processing factories. We were refused a tour on such short notice so I stealthily snuck past the lines of growers waiting for their pay into the massive, airplane hangar sized auction floor. On a walkway suspended above the floor I watched bare-chested men racing to and fro with the bursting burlap bags of tobacco on dolleys. It didn't take much coaxing for me to jump down to help out and the hall lit up with hoots as I charged with my load the length of a football field, twenty men in V-formation behind me! Really fun. The stern looking boss told me I had read my UPC code wrong and this bag was in the wrong spot. After righting this wrong he broke into a smile and told me to be in the next morning at 5 am for work. So, hey, if things don't work out when I get back to the States I always have a job waiting for me with big tobacco, at a cool $2 per day!

#1: Mother Tiger

It started as an innocent trip to go see Kazanga, a traditional ceremony of the Nkoya tribe of northwestern Zambia. Brother Rogers, Brother Peter, (former) Father Ronald and I walked a good distance out of town to the field where the festivities were being held. We didn't stay more than an hour (the crowds of drunken young men were a bit too much for my holy companions) but I did get a chance to cause a scene by joining one of the performance groups dancing in the main arena. On the way out we helped push a little pickup truck named Mother Tiger that had stalled outside the main gate. Next thing we knew we were speeding downhill back towards town. It was then that Br. Peter said he didn't think that the truck had any breaks. Fr. Ronald added that he knew the man driving as a drunk. I immediately dismissed these comments: how could this man be taxying people to and from Kazanga all day if he had no breaks? I mean, what would he do when he met someone on the one-lane bridge at the bottom of the hill?! Of course, we barreled onto the bridge with a shiny SUV already half-way across. The other driver flashed his lights and beeped the horn; since we had neither of these our driver simply started yelling out his window. As I braced myself for the impact Br. Rogers jumped overboard at a run, managing to stay both on his feet and out of the river some twenty feet below. Fortunately the other driver started to reverse so the crash wasn't too violent, with the guardrails easing us back off the bridge. Nevertheless, the grill of the new SUV was badly damaged and as the men began to push my driver for his stupidity I feared they would beat him bloody. Since everyone was unharmed they contented themselves to haul Mother Tiger and its owner into the police station. My friends and I had a good laugh after fleeing the scene of the crime. But when they began to blame the fact that the bridge only had one-lane, I had to interject. Mother Tiger had to accept at least partial responsibility. They shrugged their shoulders, afterall, this was transportation in Zambia.