Monday, September 04, 2006

Malawi

"Give me money!" "Give me sweet!" "Give me pen!" "Where is my pension?" These were the calls that followed me throughout Malawi. Not only from children either, with adults getting into the act, asking me to buy them new shoes, put them through school, or even build them a church or a school! This is not to imply that they weren't present in other countries, but they seemed especially constant in this small southern African country, self-dubbed "the warm heart of Africa" (which, I should note, in many ways it is with friendly, outgoing, hospitable people...) These pleas shouldn't be surprising given that most Malawians live on a dollar a day and that mzungus (whites) have deep (or at least relatively deep) pockets. What concerns me though is how these fairly innocent statements point to a sense of dependency on, entitlement to, and helplessness without handouts from others. That can have a very real and debilitating effect on a culture. So where does this come from? Was it from the tourists? The aid workers? To me each group seemed to be equal contributors to this problem (not an exciting prospect as I managed to qualify as both of these culprits...)

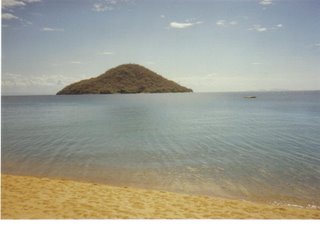

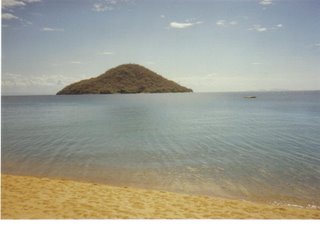

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

The mixed results of foreign aid goes back even further. For three decades western donors purposely propped up repressive dictator Dr. Hastings Banda (a product of the US education system) as a bulkhead against the otherwise socialist tendencies of the region. This is an extreme case but studies show little immediate growth and most damningly, negative results in the long term. The problem with development is that it is ultimately self-interested, coming with many strings attached. Development groups hire their own compatriots so few of their dollars or know-how trickle down to the locals in need. They focus on the sexy projects -- bridges, power-plants, etc. -- failing to provide for the equally pressing needs maintainance and renovation. So things fall apart. And all of this is approached in a top-down manner; locals are not asked what they need, but rather told what they much do. This assumes that western culture has a monopoly on the knowledge of how a society should develop (because we haven't made any mistakes...) So foreign labor, surpluses, and dollars are sunk into various holes in the country with pitiful results, which are blamed on poor execution and even a bad work-ethic on the part of the local recipients. In truth most of the blame lies with this backwards approach to giving aid, encouraging these values of dependency, entitlement, and helplessness.

As I said these are not easy revelations for me. I firmly believe in the importance of experiencing and learning about other cultures as well as the need for rich countries to commit their resources to assisting the poorer nations of the world. And I still do. Once again we must beware the false morals of cynics who would tell us to disengage entirely and instead search for a better solution. There are both good and bad ways of doing most anything; tourism and foreign aid are no exception. What we really need is to reevaluate our current approach. Tourists must be more mindful of the impact of their actions and how they spend their dollars. Aid organizations must seek solutions from the people, empowering them to help themselves. And most importantly, both must put the interest of the Malawian people first in their minds and actions that follow. At that point we foreigners may actually be able to contribute favorably, finally allowing Malawi to become independent, self-sufficient, and prosperous. In the eyes of this traveler-volunteer that would be a much nicer legacy.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.

Malawi's tourism industry has slumped significantly in recent years, seemingly coinciding with the disclosure that Lake Malawi did in fact have a high incidence rate of the disease bilharzia. But while the number tourists has decreased, the number of Malawians who are dependent on the industry has not. Evidence Cape Maclear, one-time traveler byword for fun in the sun. Now it is the definition of a backpacker ghetto, with crowds of "beachboys" pushing cheap carvings, paintings, guided trips, and, of course, everyone and their mother (literally) selling "dagga," or weed. The travelers themselves are largely to blame, many times seeming to enjoy the sleeze and failing to consider the impact of their actions on such a delicate environment. Even the well-meaning practice of giving pens, sweets, and money to kids has reprecussions with children learning dangerous lessons about race relations, becoming harder to parent, or even dropping out of school to earn more income. If this seems extreme, remember that the impact of even a few tourists adds up quickly in such an impoverished place. All this from individual travelers who generally start with good intentions -- to enjoy beautiful natural landscapes and hospitable people, learning a bit about another part of the world -- but it ultimately leads to what I see as poison for any community with the bad luck of finding itself on the tourist circuit.The mixed results of foreign aid goes back even further. For three decades western donors purposely propped up repressive dictator Dr. Hastings Banda (a product of the US education system) as a bulkhead against the otherwise socialist tendencies of the region. This is an extreme case but studies show little immediate growth and most damningly, negative results in the long term. The problem with development is that it is ultimately self-interested, coming with many strings attached. Development groups hire their own compatriots so few of their dollars or know-how trickle down to the locals in need. They focus on the sexy projects -- bridges, power-plants, etc. -- failing to provide for the equally pressing needs maintainance and renovation. So things fall apart. And all of this is approached in a top-down manner; locals are not asked what they need, but rather told what they much do. This assumes that western culture has a monopoly on the knowledge of how a society should develop (because we haven't made any mistakes...) So foreign labor, surpluses, and dollars are sunk into various holes in the country with pitiful results, which are blamed on poor execution and even a bad work-ethic on the part of the local recipients. In truth most of the blame lies with this backwards approach to giving aid, encouraging these values of dependency, entitlement, and helplessness.

As I said these are not easy revelations for me. I firmly believe in the importance of experiencing and learning about other cultures as well as the need for rich countries to commit their resources to assisting the poorer nations of the world. And I still do. Once again we must beware the false morals of cynics who would tell us to disengage entirely and instead search for a better solution. There are both good and bad ways of doing most anything; tourism and foreign aid are no exception. What we really need is to reevaluate our current approach. Tourists must be more mindful of the impact of their actions and how they spend their dollars. Aid organizations must seek solutions from the people, empowering them to help themselves. And most importantly, both must put the interest of the Malawian people first in their minds and actions that follow. At that point we foreigners may actually be able to contribute favorably, finally allowing Malawi to become independent, self-sufficient, and prosperous. In the eyes of this traveler-volunteer that would be a much nicer legacy.

Comments:

<< Home

Josh - you rock. You have posted great entries. I especially like the one about being a responsible tourist-volunteer-traveler - I couldn't agree with you more. I miss you and can't wait to see you in December! Love ya! Di :)

Well said, bro. Excellent posts thus far, I loved the anecdotes about Malawi and Zambia but really enjoy your exploits on aid and volunteerism, poverty and contradictions. Keep up the good narrating.

Post a Comment

<< Home